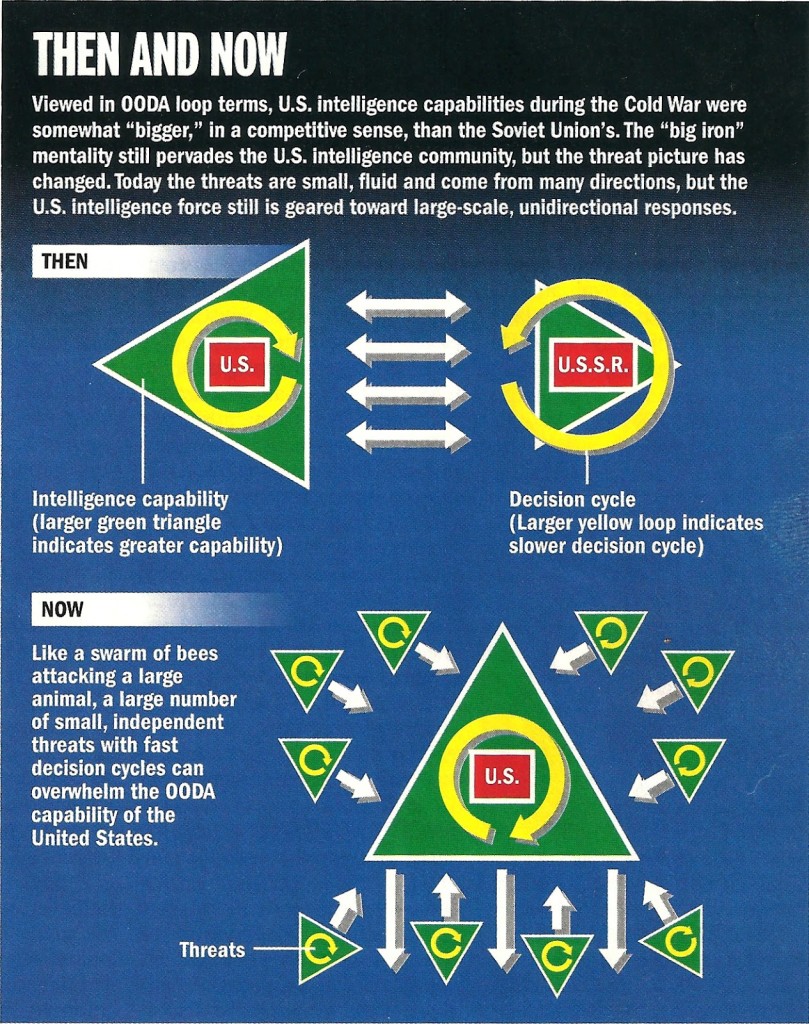

With its Code War-era organization, U.S. intelligence is overwhelmed by today’s numerous, small threats

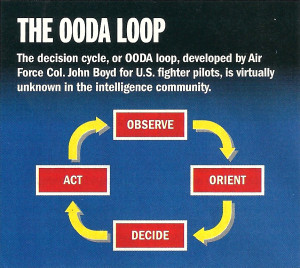

This article about decision support systems was published in the Intelligence, Surveillance & Reconnaissance Journal (May 2004). Not much has changed since then, so I thought repeating what I said back then would be as good a place as any to start this blog. Central to understanding the reasons for past intelligence failures and spiraling intelligence system costs is knowledge of the decision cycle or OODA loop (Observe Orient Decide Act) teachings of Colonel John Boyd, considered by some to be one of the foremost military thinkers of all time. The failure to fully and systematically embrace Boyd’s teaching is the root of many of the problems faced by US intelligence organizations in their attempts to adapt to today’s rapidly changing and complex information environment.

The world has changed. Today’s intelligence threats are no longer few, large, and slow; they are small, diverse, many and fecund, and are evolving at a ferocious rate. Our failure to adapt in responding is both a technical and an infrastructural problem. It comes from a failure on the part of existing technologies and intelligence organizations to consider the impact of decision cycles in any of their doings. Organizational failings are largely the result of ignorance and complacence. Technical failings are simply due to the fact that the systems to enable this approach have never existed in order to be adopted.

The world has changed. Today’s intelligence threats are no longer few, large, and slow; they are small, diverse, many and fecund, and are evolving at a ferocious rate. Our failure to adapt in responding is both a technical and an infrastructural problem. It comes from a failure on the part of existing technologies and intelligence organizations to consider the impact of decision cycles in any of their doings. Organizational failings are largely the result of ignorance and complacence. Technical failings are simply due to the fact that the systems to enable this approach have never existed in order to be adopted.Infrastructure Problems

- Be able to cycle around the loop faster than your opponent

- Disrupt the opponent’s OODA loop to cause him to slow down or make mistakes

- Alter the tempo and rhythms of your own loop so that your opponent cannot keep up

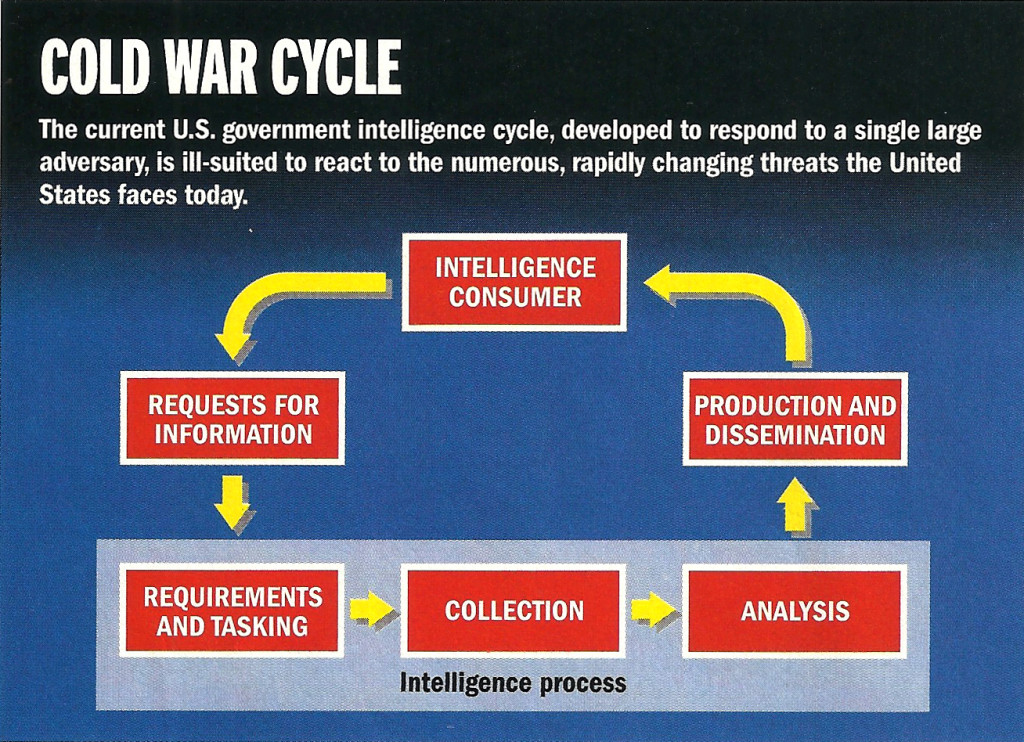

- The cycle is too slow. Indeed, it is not clear that it is a cycle at all, since most requests result in a single iteration. The existence of various organizations in the cycle and the time taken for information to pass through bureaucratic interfaces, prevent the cycle from keeping up with events.

- It is essentially command-driven, and thus only allows looking into questions that the intelligence consumer already ‘knows’ to ask. But an effective cycle must support the discovery of things you didn’t even know were important. The consumer cannot anticipate all possible threats and task the complete cycle to investigate each.

- The lack of feedback between the consumer and the analyst, and the inability of the consumer to directly examine backup material behind analytical conclusions, can cause the final product not to meet the consumer’s needs.

The community’s failure to move to a modern cycle is primarily due to a failure to adapt to the post-Cold-war world in which the enemy is no longer the U.S.S.R. but a diverse, loosely coupled, and rapidly adapting amalgam of terrorist organizations and other assorted bad guys. Only a fraction of the problem now relates to threats posed by sovereign states.

The community’s failure to move to a modern cycle is primarily due to a failure to adapt to the post-Cold-war world in which the enemy is no longer the U.S.S.R. but a diverse, loosely coupled, and rapidly adapting amalgam of terrorist organizations and other assorted bad guys. Only a fraction of the problem now relates to threats posed by sovereign states.In the good old days of the Cold War, U.S. capabilities to gather and act on intelligence were somewhat better than Soviet Union’s. In a competitive sense, the U.S. was ‘bigger’. More importantly, the Soviets were hampered by a hopelessly slow and ineffective decision cycle caused by bureaucracy and a pervasive culture of distrust throughout the organizational pyramid. With both capability and adaptability in its favor, the U.S. community, oblivious of OODA loops, gradually settled into a culture of confidence and complacency. From these roots came the “big-iron” mentality (same again but super-size me!) that pervades the intelligence community.

We can imagine our ideal intelligence organization consisting of a large triangle composed of many smaller triangles, each able to swivel independently to orient itself and empowered to separately track potential foes. Each triangle can rapidly pass its findings through the hierarchy to decision-makers and simultaneously to the “swatter” – the U.S. military. If we could only track, target, and decide to swat our foes, we certainly have the power to do the swatting.

The intelligence community, with its intense security ethos and somewhat insular mindset, naturally falls prey to these problems at a higher rate than any other branch of government. Furthermore, government imposes so many hurdles on the participation of small, nimble information companies, ranging from its security requirements, to its outmoded development models, that it is almost impossible for the community to take advantage of these companies, which either starve, or are swallowed up by the larger vendors to acquire technology. Regrettably the larger entity just gets fatter; it seldom acquires any of the nimbleness of its prey.

The intelligence community, with its intense security ethos and somewhat insular mindset, naturally falls prey to these problems at a higher rate than any other branch of government. Furthermore, government imposes so many hurdles on the participation of small, nimble information companies, ranging from its security requirements, to its outmoded development models, that it is almost impossible for the community to take advantage of these companies, which either starve, or are swallowed up by the larger vendors to acquire technology. Regrettably the larger entity just gets fatter; it seldom acquires any of the nimbleness of its prey. All these factors mean the government is isolated from the best advances in the information realm and must make do with a sort of distillate of such advances secreted by the usual large vendors. It is not surprising then, that information systems provided to, or specified by, the government are generally obsolete at the time they are delivered, or shortly thereafter.

Decision Support Systems – Technology Problems

- Data-level systems contain large amounts of data points concerning the target domain but have not yet organized this data into a human-useable form. Such systems are primarily found during the ingestion phase.

- Information-level systems have taken the raw data and placed it into tables that can be searched and displayed by the system users. The overwhelming majority of today’s systems operate in this realm.

- Knowledge-level systems have organized the information into richly interrelated forms tied directly to a mental model or ontology that expresses the kinds of things being discussed and the interactions that are occurring between them. Few systems today operate at this level, but those that do allow their users to find ‘meaning’ in the information they contain.

- Wisdom-level systems allow users to view new knowledge against past knowledge, to see patterns, and to predict the intent of entities of interest those patterns might imply. Unfortunately, there are no Wisdom-level systems in existence for any generalized domain. Wisdom remains the exclusive purview of system users.

- Observe. Acquiring knowledge from as many sources as possible as fast as we can is a Data-level undertaking. We can now gather observations on a global scale, and with a fidelity and diversity that is almost beyond comprehension. No problem here.

- Act. To act we must provide easily understood Information to those that must act. The tools available to the U.S. to act, should it choose to, are without equal. No problem here either.

- Orient. To orient, we must place observations in the context of all others, in preparation for a decision. Here we have a problem. Orientation not only requires converting every source into a unified whole to be searched consistently by users (an Information level problem), but also, given the massive diversity in source formats, we must convert into a common “ontological” form so that the users can efficiently compare meaning. This requires a Knowledge-level system, but few such systems exist, and none operate on a general domain such as intelligence. Technology has failed us. The state of affairs at this time is that our agencies have thousands of mostly archaic, isolated, Information-level systems (or stovepipes), each focusing on a single source or problem area. Worse yet, system output is not available to everyone that needs it, and for those that do have it, the interface to each is different, overloading our analysts as they try to integrate in their head all that they have seen to find meaning. Thus analysts spend the majority of their time in the mechanics of accessing the data, and only a tiny fraction in actual analysis (or Orientation). The solution we adopt is to add people, thousands upon thousands of them, to try to close this portion of the loop.

- Decide. Decisions require Wisdom. We must evaluate our new knowledge against past experience and patterns, determine what these new patterns mean, and then model the potential consequences of our actions on the outside world and the OODA loops of our enemies. None of these steps is even partially supported by today’s systems, certainly not in a manner that is tightly linked to the entire OODA loop and allows free intermixing of modeling information with real-world data. Yet this is the nature of Wisdom. Finding no solution to this problem either technically or organizationally, people have simply learned to live with it.

In addition to problems with each step in the loop, a meta-problem exists: Even if we could grease the inner wheels of each step more effectively, we have no axle to turn our overall OODA wheel. For information to flow around the cycle rapidly, recursively, and effectively, all participant systems must pervasively communicate with all others. We need one community-wide ontology-based system, operating at all four levels, and allowing all portions of the loop to interact with information, validate each other’s conclusions and introduce new knowledge into the cycle.

In addition to problems with each step in the loop, a meta-problem exists: Even if we could grease the inner wheels of each step more effectively, we have no axle to turn our overall OODA wheel. For information to flow around the cycle rapidly, recursively, and effectively, all participant systems must pervasively communicate with all others. We need one community-wide ontology-based system, operating at all four levels, and allowing all portions of the loop to interact with information, validate each other’s conclusions and introduce new knowledge into the cycle. The dinosaurs ruled the earth for 120 million years. They are all gone. They failed to adapt to change. In the information world, timeframes are infinitely shorter and change immeasurably faster. Our intelligence infrastructure has ruled unchallenged since the 1940s, but the world is changing. Let’s not make the same mistake as the dinosaurs.

The dinosaurs ruled the earth for 120 million years. They are all gone. They failed to adapt to change. In the information world, timeframes are infinitely shorter and change immeasurably faster. Our intelligence infrastructure has ruled unchallenged since the 1940s, but the world is changing. Let’s not make the same mistake as the dinosaurs.